Digital tools for optimising diabetes self-management

Self-management of diabetes requires patients to regularly monitor and interpret their diet, exercise and blood glucose levels and can become burdensome in the long term. Judicious use of digital tools may help patients to better and more easily manage their diabetes and live healthier lives.

- Many digital tools are available to aid people in self-managing their diabetes, but some are more helpful and evidence-based than others.

- Several mobile applications, including some integrated with blood glucose meters, have been shown to have positive outcomes on HbA1c levels, hypoglycaemia incidence and diabetes self-management skills.

- For people with diabetes, social media can provide a valuable connection to other people living with the condition.

- Wearable fitness devices can provide personalised health data, which may assist with behaviour change.

- Telehealth and remote telemonitoring show promise for providing care to patients with diabetes.

- The growth in ‘big data’, genomics and artificial intelligence systems is likely to contribute to evolutionary changes in the management of diabetes.

- Practitioners should apply due diligence regarding digital self-management tools but not be afraid to support and engage patients in using this technology.

Optimal self-management of diabetes requires regular monitoring and analysis of diet, exercise and blood glucose levels, followed by informed decision making. Patients require extensive education to be able to self-manage their diabetes and, in the long term, self-management can be difficult and tedious to maintain. However, an extensive range of available digital tools may help. There is much enthusiasm for the potential benefits these tools offer people with diabetes, but some offerings may be more distracting than helpful. This article will explore the variety of digital health tools available to aid in diabetes self-management and how they can best be used.

How digitally connected are Australians?

Australians are some of the most digitally connected people in the world, with 92% of our population using the internet1 and 80% owning a smartphone.2 These smartphones are not sitting idly in pockets or on tables; on average, Australians check their smartphones more than 30 times a day.2 In addition to our insatiable appetite for smartphones, we also have a national thirst for electronic tablets, fitness trackers and smartwatches. With so many of us ‘connected’, there is an opportunity for access to a world of digital tools that can enable improved health.

It is easy to assume that it is the younger members of the population who are using all the bandwidth of connectivity. However, data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics indicated that 68% of older Australians (aged over 65 years) used the internet in the 6 months to May 2014,1 with this figure expected to continue growing. The use of smartphones and tablets by older adults is also on the rise, with their usage focused on social media, news and instant messaging. It is therefore important not to dismiss the willingness of older people to use technologies that are familiar to them to assist with managing their health care.

The wisdom and worries of the web

It is almost inevitable that patients will google their diagnosis or symptoms before they visit a clinic. A search on the term ‘diabetes’ will produce no fewer than 249 million websites, containing a variety of information. Once the internet surfer navigates past any initial sponsored links, the websites of Diabetes Australia, the Australian Diabetes Society and the National Association of Diabetes Centres, as well as relevant state and federal government sites, are, thankfully, often ranked highest in the results of a web search for diabetes. However, beyond this, the murky waters of unscientific remedies start to rise in the search results.

Organisations that provide reputable information for patients with diabetes include:

- Diabetes Australia (www.diabetesaustralia.com.au)

- state and territory offices of Diabetes Australia (see website for links), for local education and support groups healthdirect (www.healthdirect.gov.au/diabetes)

- diabetes research institutes with information on resources, new research and opportunities to participate in trials, such as the Baker Heart & Diabetes Institute (www.baker.edu.au) and Garvan Institute of Medical Research (www.garvan.org.au).

To guide patients to reputable websites with quality information and resources, links can be given in handouts, emailed to patients or linked from the clinic’s own website.

An app a day?

Several systematic reviews of health care mobile applications (‘apps’) have supported the value of this technology.3 However, there are caveats, as not all apps are created equal.4 With more than 1000 diabetes-specific apps on the market, it is important to know what to choose.

Before suggesting the use of an app to aid with diabetes self-management, it is important to ascertain:

- if the patient has a smartphone or tablet

- if the patient is familiar and confident with using apps

- what tools would be helpful for the patient

- which app or apps would best meet the individual needs of the patient.

The patient needs to already have a smartphone or tablet and be comfortable with using apps, because without an existing level of competence and confidence, extensive training and support – which are not usually in the remit of a practice and its staff – may be needed.

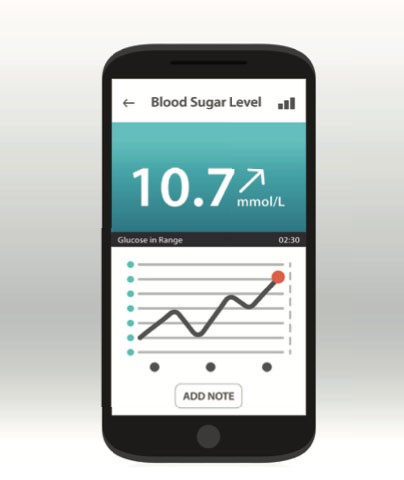

An understanding of what tools and supports (if any) would add value to the patient’s self-management is also crucial. Does the patient have trouble remembering to take medication? An app to remind them to do so could be of value. Does the patient measure blood glucose levels but not record them in a diary? An app with Bluetooth connectivity to the blood glucose meter to automatically upload, sort and present data in a graphical format that can be shared with the patient’s healthcare team could be the solution.

Evolution of the app market is rapid and the sophistication and benefits of some apps are growing. Although not yet available in Australia, a good example is the BlueStar Diabetes app, designed for patients with type 2 diabetes by an experienced health professional-based team in the USA. After the patient’s medical history, medication and clinical data are uploaded, the app’s sophisticated behavioural and clinical analysis systems deliver real-time, personalised content to guide self-management decisions. Its use has been shown to lead to reductions in HbA1c levels of up to 2.03%.5 The app learns over time and adapts to the patient and allows patients to send information to their health care providers to enable further support. It is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (required because of the potential risks associated with decision support software tools) and is only available by prescription in the USA. Clinician input can ensure that decision support tools are correctly tailored to the patient.

A review of evidence-based diabetes decision support apps found that some can assist in behaviour change and facilitate appropriate treatment adjustments, which may positively affect clinical outcomes and quality of life (Table 1).6-14

What to look for in app design

Apps that support diabetes self-management may focus on diet, exercise, medication management, sleep, relaxation, other factors or a combination of these. As there are many apps of varying quality to choose from in each of these categories, it is good to keep in mind some simple rules:

- be clear what tool is needed – what technology, if any, could be used to aid the patient’s health goals?

- research the app – read reviews and search online to see what people say about it

- find out who developed the app – are they health professionals or linked to a reputable organisation?

- road test the app – not all apps do as they promise; some are glitchy, hard to use and simply become annoying

- look for simplicity – apps that are simple to use and synchronise with other health data are often used for longer

- check privacy – find out how collected information is kept and read the fine print.

The top 10 health apps for people with diabetes (as trialled and selected by the first author) are shown in Table 2.

Social media

For people with diabetes, social media can provide a valuable connection to other people living with the condition.15 Sharing experiences, knowledge and feelings, whether face-to-face or online, can have positive outcomes for all those involved.16 Peer-to-peer interactions can give people living with a chronic condition such as diabetes a sense of comfort that they are not alone, that what they are going through physically and psychologically is not unusual and that they can seek help when needed. This significantly improves the quality of life of the person with diabetes.17 Research supports the use of a range of social media platforms,18,19 although similar warnings apply as for other online platforms: connections should be made with reputable groups that have the backing of, or links with, health-based organisations or qualified health professionals.

One Australian example is the Oz Diabetes Online Community (#OzDOC), a diabetes support group run on the Twitter platform under the auspices of Diabetes Australia. Members of the online group connect every Tuesday at 8.30 pm AEST and are guided through an online chat by either the moderator, who has type 1 diabetes, or a guest, who may be a health professional. The one-hour forum is insightful, supportive and positive.

Another Australian online resource is Diabetes Can’t Stop Me (www.diabetescantstopme.com). The website, run by blogger Helen Edwards who has type 1 diabetes, offers articles, blog posts and information about living with diabetes and the psychosocial issues encountered. Some of this content has been rehoused from its former site, Diabetes Counselling Online. An offshoot of this is the Diabetes Can’t Stop Me group on Facebook, which is a forum for members to talk about living with diabetes, rather than a support group, counselling service or provider of medical advice.

Wearables

Wearable fitness devices are a growing trend, but do they lead to increased levels of activity over the long term and therefore have a positive impact on the health of a person with diabetes? Unfortunately, there is no clear answer to this question, as it depends on many factors.

Some elements of success come down to the device being user-friendly and appropriate for the age and fitness level of the person wearing it. There is little value in giving a high-end smartwatch designed for a triathlete to an 80-year-old person who walks regularly. Conversely, a non-Bluetooth pedometer may be useless for someone who swims and cycles for fitness. Furthermore, research indicates that those who wear these devices for longer than six to 12 months, the time frame in which many people stop using them, are usually those who were already focused on their health, disciplined and doing regular exercise.20

Despite this, there is some value in finding the right wearable tool for a person with diabetes. It is well established that exercise and weight loss can lead to better diabetes management. As wearable technology has been shown to increase activity levels of users and to aid in weight loss,21 it would be expected to also lead to better diabetes management. Whether the wearable device is simple or sophisticated, insights into movement, sleep and steps taken in a day can be valuable opportunities to add more detail to the picture of diabetes self-management.

Smartwatches are also now making their mark in the management of diabetes,22 and recent media reports suggest that wearable devices that can noninvasively measure blood glucose levels are in development. Such technology, if successfully implemented, would be a huge advance in the field.

Telehealth

Although research into the benefits of telehealth is relatively nascent, recent systematic reviews suggest that mobile apps and telemedicine can have positive effects on blood glucose levels.23,24 Despite the Australian Government’s introduction of telehealth funding in 2011 to support access to specialist services for those living in rural and remote areas, uptake of telehealth nationally has been slow.25

Diabetes is an almost perfect condition for telehealth, because consultations are based on interaction and do not always require physical examination of the patient. Many diabetes specialists and GPs who have embraced this technology report a high level of success for those involved, including patients.26

The Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine website has a telehealth provider directory listing practitioners of different disciplines, including endocrinology, who provide telehealth services (www.ehealth.acrrm.org.au/provider-directory). The Royal Flying Doctor Service Victoria provides guidelines for GPs running a telehealth service (www.flyingdoctor.org.au/vic/our-services/diabetes-telehealth-services).

Remote telemonitoring

A newer and lesser known player in the health technology field is the remote telemonitoring device. These devices are now available through health provider organisations, such as the Royal District Nursing Service and Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA), and some health insurance companies. A tablet with wireless internet and Bluetooth connections enables data to be uploaded from devices that measure parameters such as blood glucose level, oxygen saturation, blood pressure and heart rate. This information is then presented to the organisation’s health professional team, who review and interpret the data and provide self-management education and support. The tablets also serve as telehealth units, enabling remote consultations between the patient and clinician.

GPs in various locations across Australia had the opportunity to offer this service to DVA patients as part of the In-Home Telemonitoring for Veterans Trial between June 2013 and December 2016.27 Results of the trial are expected soon. However, those interested in using this newer technology may find that the Health Care Homes program (to be introduced from 1 October 2017) will support funding for more bespoke models of care, such as remote telemonitoring.

Emerging health technology trends

Personalisation of medicine is a hot topic, and for good reason. Every individual responds differently to treatments, as a result of factors including genetics, environment, income, health literacy, diet and activity. The ‘one-size-fits-all’ healthcare system is losing the war against chronic disease, and technology offers a not-so-distant solution to better understanding the individual.

The use of genomics is growing and becoming more affordable in mainstream medicine. The ability to review an individual’s DNA sequence and determine genetic mapping provides extensive insights into diseases, including diabetes. Pharmacogenomics, which uses patients’ genetic information to select the most effective medications for treatment, will also develop over time.

Future health care is expected to noticeably improve through the ongoing use of ‘big data’, also known as machine learning. Through the collation of information from around the world, cognitive computing systems, such as IBM Watson, can, for example, crunch all the available data on cancer and its treatments and provide the clinician with an evidence-based, individualised management regimen for each patient.28 Machine learning has also been used in providing better treatment for people with type 2 diabetes.29 Such systems will continue to evolve and be integrated into existing patient management software as clinical decision support tools.

Funding of health technology

One of the major barriers preventing health care professionals’ uptake of newer technologies has been the challenge of reimbursement for the time invested in reviewing and interpreting data and providing feedback to patients. Australian funding models have been a limiting factor in using innovative technology options in primary health care and, as such, have deterred adoption of patient-facing technologies.

A paradigm shift in funding models is required if digital health is to reach its fullest potential in Australian healthcare systems. The reforms being introduced with the Health Care Homes funding model offer some hope that this may occur. Without a review of health care reimbursements, there will be an ongoing risk that innovative healthcare services will be stifled and significant opportunities for improvement lost.

Conclusion

Health technologies have the potential to provide people with diabetes more services, more extensively and at a much lower cost. To do this effectively, the electronic tools need to make life easier for both the patient and the clinician and offer solutions to existing challenges. Digital health tools need to be personalised to the patient and understood and supported by the healthcare professional. To do this successfully, there will need to be a significant shift in healthcare funding models.

Technology will never be a panacea for diabetes or any other health condition. Human interaction will always be at the cornerstone of diabetes self-management. Nevertheless, existing and emerging technologies offer a range of valuable tools that health clinicians and patients alike should consider adding to their toolbox. The National Association of Diabetes Centres will be holding the first Australasian Diabetes Advancements and Technologies Summit (nadc.net.au/adats) in Sydney on 20 October 2017 to discuss how technology can assist both health professional and patient to achieve better outcomes.

References

- Australian Communications and Media Authority. Communications report 2013–14 series: report 1–Australians’ digital lives. March 2015. Melbourne: Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Communications and Media Authority); 2015.

- Deloitte. Mobile Consumer Survey 2015: the Australian cut. Sydney: Deloitte; 2015.

- Mosa ASM, Yoo I, Sheets L. A systematic review of healthcare applications for smartphones. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012; 12: 67.

- Baig MM, GholamHosseini H, Connolly MJ. Mobile healthcare applications: system design review, critical issues and challenges. Australas Phys Eng Sci Med 2015; 38: 23-38.

- Quinn CC, Clough SS, Minor JM, Lender D, Okafor MC, Gruber-Baldini A. WellDoc mobile diabetes management randomized controlled trial: change in clinical and behavioral outcomes and patient and physician satisfaction. Diabetes Technol Ther 2008; 10: 160-168.

- Drincic A, Prahalad P, Greenwood D, Klonoff DC. Evidence-based mobile medical applications in diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2016; 45: 943-965.

- Sussman A, Taylor EJ, Patel M, et al. Performance of a glucose meter with a built-in automated bolus calculator versus manual bolus calculation in insulin-using subjects. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012; 6: 339-344.

- Niel JV, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn PH; Dutch Insulinx Study Group. Use of a smart glucose monitoring system to guide insulin dosing in patients with diabetes in regular clinical practice. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2014; 8: 188-189.

- Ziegler R, Cavan DA, Cranston I, et al. Use of an insulin bolus advisor improves glycemic control in multiple daily insulin injection (MDI) therapy patients with suboptimal glycemic control: first results from the ABACUS trial. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 3613-3619.

- Barnard K, Parkin C, Young A, Ashraf M. Use of an automated bolus calculator reduces fear of hypoglycemia and improves confidence in dosage accuracy in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus treated with multiple daily insulin injections. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012; 6: 144-149.

- Charpentier G, Benhamou PY, Dardari D, et al. The Diabeo software enabling individualized insulin dose adjustments combined with telemedicine support improves HbA1c in poorly controlled type 1 diabetic patients: a 6-month, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, multicenter trial (TeleDiab 1 Study). Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 533-539.

- Franc S, Borot S, Ronsin O, et al. Telemedicine and type 1 diabetes: Is technology per se sufficient to improve glycaemic control? Diabetes Metab 2014; 40: 61-66.

- Skrovseth S, Arsand E, Godtliebsen F, Joakimsen RM. Data-driven personalized feedback to patients with type 1 diabetes: a randomized trial. Diabetes Technol Ther 2015; 17: 482-489.

- Rossi MC, Nicolucci A, Lucisano G, et al. Impact of the “Diabetes Interactive Diary” telemedicine system on metabolic control, risk of hypoglycemia, and quality of life: a randomized clinical trial in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2013; 15: 670-679.

- Toma T, Athanasiou T, Harling L, Darzi A, Ashrafian H. Online social networking services in the management of patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014; 106: 200-211.

- Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, Carroll JK, Irwin A, Hoving C. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15: e85.

- Trawley S, Browne JL, Hagger VL, et al. The use of mobile applications among adolescents with type 1 diabetes: results from Diabetes MILES Youth-Australia. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016; 18: 813-819.

- Leahey T, Rosen J. DietBet: a web-based program that uses social gaming and financial incentives to promote weight loss. JMIR Serious Games 2014; 2: e2.

- Majeed-Ariss R, Baildam E, Campbell M, et al. Apps and adolescents: a systematic review of adolescents’ use of mobile phone and tablet apps that support personal management of their chronic or long-term physical conditions. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17: e287.

- Piwek L, Ellis DA, Andrews S, Joinson A. The rise of consumer health wearables: promises and barriers. PLoS Med 2016; 13: e1001953.

- Jakicic JM, Davis KK, Rogers RJ, et al. Effect of wearable technology combined with a lifestyle intervention on long-term weight loss: the IDEA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016; 316: 1161-1171.

- Arsand E, Muzny M, Bradway M, Muzik J, Hartvigsen G. Performance

- of first combined smartwatch and smartphone diabetes diary application study. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015; 9: 556-563.

- Bonoto BC, de Araujo VE, Godoi IP, et al. Efficacy of mobile apps to support the care of patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017; 5: e4.

- Faruque LI, Wiebe N, Ehteshami-Afshar A, et al. Effect of telemedicine on glycated hemoglobin in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. CMAJ 2017; 189: E341-E364.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Telehealth quarterly statistics update. Canberra: Department of Health; 2016. Available online at: http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/connectinghealthservices-factsheet-stats (accessed June 2017).

- Fatehi F, Gray LC, Russell AW, Paul SK. Validity study of video teleconsultation for the management of diabetes: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Technol Ther 2015; 17: 717-725.

- Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs. In-Home Telemonitoring for Veterans Trial. Canberra: Department of Veterans’ Affairs; 2016. Available online at: http://www.dva.gov.au/providers/provider-programmes/home-telemonitoring-veterans-trial (accessed June 2017).

- Guinney J, Wang T, Laajala TD, et al. Prediction of overall survival for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: development of a prognostic model through a crowdsourced challenge with open clinical trial data. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: 132-142.

- Ozery-Flato M, Ein-Dor L, Parush-Shear-Yashuv N, et al. Identifying and investigating unexpected response to treatment: a diabetes case study. Big Data 2016; 4: 148-159.